An artist that exemplifies redemption is Vik Muniz, who specializes in photographing unique physical creations and displaying them as enlarged photographs. Looking at one of Muniz’s photographs from afar, it looks like a regular image or a rendering of a familiar piece of artwork, but when examined up close, one discovers the use of various and surprising mediums, like chocolate syrup, peanut butter and jelly, plastic toy soldiers, and garbage. Muniz takes trash and discarded rubbish and transforms them into something beautiful, exemplifying the act of redemption.

In the movie Waste Land, Vik Muniz takes a journey back to his homeland of Rio De Janeiro in order to meet those who live and work at Jardim Gramacho, the world's biggest garbage landfill.

As his helicopter first flies over the terrain of the landfill, he sees the hundreds of people working like ants, digging through the trash heaps picking out items that can be sold to recycling companies. He assumes that the “pickers” must be savages, filled with bitterness and violence.

As Muniz begins to talk with the people, getting to know their stories, he finds that the human spirit to more than just survive but to flourish, to find meaning and hope, is alive and well. There’s Tiaõ, the young, energetic president of the Association of Recycling Pickers of Jardim Gramacho. He has been a picker since he was eleven, and hopes that the fledgling union will grow in influence in order to improve the lives of the pickers. There’s Suelem, a young woman of eighteen who has been working on the garbage heap since she was seven. She has two kids and is pregnant with a third, but she is actually proud of the hard work she does at the landfill, because she has not taken the route of prostitute that she has seen many other pretty young women take.

Muniz convinces these pickers that they should let him take photographs of them in order to create his artwork. They understand that Muniz is a world-renowned artist whose artwork sells for incredible amounts of money. Muniz explains to them that by cooperating with him, he will be able to give them and their difficult work the recognition it deserves and that he will donate all the proceeds from his portraits back to the pickers.

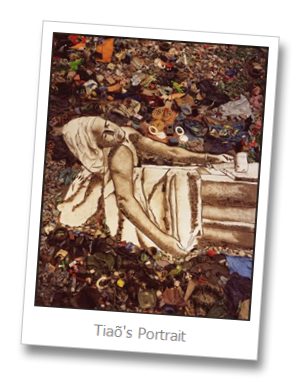

Muniz takes portraits of the pickers in different fascinating poses, and then blows up the black-and-white images to the size of the floor of a large warehouse. In the next step of the process, Muniz has the pickers help him fill in the details of the images on the floor with all sorts of discarded trash items that the pickers have saved from the landfill for recycling. There’s old sodapop bottles, toilet seats, plastic bins, traffic cones, shoes, etc., meticulously placed in such a way that the portrait takes shape through the objects. Muriz then takes a high-resolution photograph of the final project, and frames the large portrait for display.

Tiaõ accompanies Muniz to the art auction for the portraits, where the portrait featuring himself follows a piece by Andy Warhol. The final bid for the portrait was $50,000!

Tiaõ accompanies Muniz to the art auction for the portraits, where the portrait featuring himself follows a piece by Andy Warhol. The final bid for the portrait was $50,000!As Tiaõ is overwhelmed and weeps and Muniz hugs him, we experience in a very real, cathartic way the pleasure of redemption.

Tiaõ has been recognized for the work he has been doing since he was a little boy, and he now has the money to make his union flourish in order to bring dignity to the work of the pickers back at Jardim Gramacho.

Art can move us to see redemption in real, physical existence. The stuff of art is the stuff of our existence, whether it is paint squeezed out of a tube, or refuse discarded at a giant garbage dump.

When art tells the story of redemption, it is tapping into the truth of the cosmos – that God created this world as it ought to be, that things are broken and not the way it should be, but that something needs to be done about it so that there can be hope for the future. The artist, whether he knows it or not, is retelling the grand narrative of Creation-Fall-Redemption-Restoration, the truth of the gospel found in Jesus Christ revealed in the Scriptures.

“Because we know that this creation is the good gift of God, we are not only permitted but encouraged to enjoy it as is. Unlike those who think that worldly objects are somehow enhanced by stamping Scripture verses on them, Christians who understand the goodness of this world celebrate the freedom to enjoy God’s creation as is…

“Because we know that this creation is the good gift of God, we are not only permitted but encouraged to enjoy it as is. Unlike those who think that worldly objects are somehow enhanced by stamping Scripture verses on them, Christians who understand the goodness of this world celebrate the freedom to enjoy God’s creation as is…

“When an unbelieving poet makes use of an apt metaphor, or when a foul-mouthed major league outfielder leaps high into the air to make a stunning catch, we can think of God as enjoying the event without necessarily approving of anything in the agents involved – just as we might give high marks to a rhetorical flourish by a politician whose views on public policy we despise.” (p. 37)

“When an unbelieving poet makes use of an apt metaphor, or when a foul-mouthed major league outfielder leaps high into the air to make a stunning catch, we can think of God as enjoying the event without necessarily approving of anything in the agents involved – just as we might give high marks to a rhetorical flourish by a politician whose views on public policy we despise.” (p. 37)