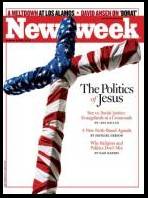

Which article seems more Christian? Which article best exemplifies the attitude of Christ? The first is from a philosopher at Baylor University, the second from a philosopher at Calvin College.

The Case of Ted Haggard

By Francis J. Beckwith

The American Spectator 11/7/2006

In the tragic case of Pastor Ted Haggard, an ever-expanding number of liberal writers and bloggers are cheerfully celebrating the fall of this man.

But it seems to me that if one looks at the life and practice of the great critic of hypocrites, Jesus of Nazareth, who is recognized by most everyone, liberal and conservative alike, as a paradigm of personal virtue, one does not find Jesus finding satisfaction or joy in the failure of others. In fact, to find comfort in another's suffering, and then to brag about the acquisition of that comfort in a public venue, seems far more wicked than the initial hypocrisy.

Remember that for Jesus, hypocrisy was a vice found in the hearts of those who thought they were spiritually and morally superior to others. Read carefully some of Jesus' most well-known comments on hypocrisy and public piety:

- Stop judging, that you may not be judged. For as you judge, so will you be judged, and the measure with which you measure will be measured out to you. Why do you notice the splinter in your brother's eye, but do not perceive the wooden beam in your own eye? How can you say to your brother, 'Let me remove that splinter from your eye,' while the wooden beam is in your eye? You hypocrite, remove the wooden beam from your eye first; then you will see clearly to remove the splinter from your brother's eye. (Matthew 7:1-5 NAB)

- (But) take care not to perform righteous deeds in order that people may see them; otherwise, you will have no recompense from your heavenly Father. When you give alms, do not blow a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets to win the praise of others. (Matthew 6: 1-2a NAB)

For Jesus, hypocrisy is clearly wrong, but it is a wrong intimately tied to a type of moral and spiritual triumphalism, just the sort that one finds in the writings of those who gleefully celebrate the moral failings of Pastor Haggard. Those who think of the detecting and condemnation of hypocrisy as sport, which is the dominant understanding of the liberal-secular chattering class, are not serious about the wrongness of hypocrisy. For such seriousness requires a tragic understanding of the human condition, that one is just as susceptible to sin's temptation as any other, and that it is only by God's grace and the support of the church that we can find forgiveness, redemption, and the strength to carry our cross. But the liberal-secular chattering class does not believe any of this. So, their detection and condemnation of hypocrisy is disingenuous at best and mean-spirited at worst.

But why would anyone think hypocrisy wrong? Of course, Christian, Jews, and Muslims can point to the clear teaching of their scriptures on this matter. More sophisticated theists may also make a natural law argument, that human beings are designed in such a way that certain acts, behaviors, and thoughts, including hypocrisy, are inconsistent with the acquisition of our personal virtue and thus our good. So, it makes sense for Jesus to condemn the hypocrite, for Jesus no doubt held that a good soul was better than a good reputation, and if one were to have the latter it should be the result of the former.

But it's not clear to what a typical liberal-secularist could appeal in order to condemn hypocrisy. He could, I suppose, argue that all he is doing is pointing out that the hypocrite is living inconsistently with his moral theology. But that's just an observation, not a judgment. After all, if the hypocrite were a religious cannibal who preached the virtues of cannibalism every Sunday and yet in private chose to abstain from his theology's culinary demands, most of us would praise, rather than condemn, the hypocrite's "hypocrisy." So, for the liberal-secularist, as with the Christian, not all cases of "hypocrisy" are per se wrong. In fact, in some cases we would prefer that people live inconsistently with what they preach, because what they preach is so horrid that it is better that we leave them undisturbed with their hypocrisy than draw their attention to it. For one way to correct the inconsistency is for the hypocrites to begin practicing what they preach. God forbid.

So, how does the liberal-secularist find warrant for his moral judgment that hypocrisy is wrong? I do not know. He cannot appeal to the scriptures of the great theistic faiths, for it is in those very texts that his political adversaries find condemnation of those activities that he considers morally benign, such as atheism, homosexuality, and fornication. What about a natural law argument, one that offers an understanding of human beings as designed agents that have an end or good that can only be achieved by certain virtues and practices? But now he's on the turf of those who appeal to the natural law to condemn homosexuality. After all, could not the hypocrite, like the liberal-secularist who defends homosexuality as a congenital property well-suited for the constitutions of those who have it, argue that the hypocrite was born with his hypocrisy, that it is deeply connected to his identity, that his personal religious beliefs do not condemn hypocrisy, and/or that he enjoys the fellowship and friendship of other similarly-situated hypocrites. And besides, who are you to judge? Waxing Darwinian, which would no doubt impress Richard Dawkins, the hypocrite could argue that hypocrites have always been with us, and so perhaps it is evolutionarily helpful to the species to have a certain number of them in our population. It seems, then, that the liberal-secularist's worldview is bereft of resources by which he may condemn hypocrisy as morally wrong.

Sadly, the liberal-secularlist does not, indeed cannot, see hypocrisy as tragic, as Jesus did. And, worse still, he cannot give an adequate moral account of why hypocrisy is wrong. Thus, it must be something less than noble that rouses the liberal-secularlist to joyfully draw others' attention to the foibles of hypocrites. Perhaps by finding fault in Jesus' pretended followers, the liberal-secularist thinks he can mollify his nagging doubt that Jesus may have indeed been right that we live in a moral universe? Perhaps. But, as we have seen, it cannot be because the liberal-secularist has a serious moral understanding of the human condition.

Christians and other theists do not have the same luxury to plead ignorance. We are both constrained and liberated by the awful truth about ourselves, and for this reason we must humbly pray, "But, for the grace of God, go I."

Francis J. BECKWITH is Associate Professor of Church-State Studies, Baylor University, as well as President-Elect of the Evangelical Theological Society. His latest book is (with W. L. Craig and J. P. Moreland) To Everyone Answer: A Case for the Christian Worldview (InterVarsity Press, 2004).

_______

Praying for Ted

by James K. A. Smith

Fors Clavigera 11/4/2006

This morning, while trying to undo autumn's leafy deposits across the backyard, I found myself--much to my surprise--praying for Ted Haggard. To be sure, Haggard represents almost everything I loathe about the Religious Right and the Babylonian captivity of evangelicalism (captured so well in Jeff Sharlet's Harper's piece a while back). And news of these allegations has made leftist bloggers just downright giddy.

But it's curious how this explosion in Haggard's life could be a reminder that, despite our political differences, Ted Haggard is still a brother. (And maybe this is a tiny little confirmation that, despite all my protests to the contrary, I'm still an evangelical.) Recent video of Haggard in his SUV, with his wife in the passenger seat, was one of the most painful snippets I've seen in a while. Forced to revise his story (I think common sense should tell us to expect further revisions), Haggard's tired eyes keep darting to his wife's face as he has to confess to compromises and failures (the camera's gaze is almost merciful in not showing her face).

While sociologists are constantly looking for the defining features of "evangelicals," I wonder if the Haggard case might provide a more visceral criterion: if you see what Haggard and his family are going through, and are moved to consider their pain, and have a haunting but persistent sense that "there, but for the grace of God go I"--then you're an evangelical. Evangelicals in their best moments are painfully aware of the brokenness of our world, and of our very selves--even our redeemed selves. And thus struggle to answer the Spirit's call to "weep with those who weep" (Rom. 12:15).

"Let him who thinks he stands take heed lest he fall" (1 Cor. 10:12).

James K.A. Smith is Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Calvin College and a Fellow of the Center for Social Research at Calvin.

technorati: politics, spiritual formation, emerging church, technorati: social action

Peace is the Hebrew word, “Shalom”—one of the most significant words in the Hebrew language.

Peace is the Hebrew word, “Shalom”—one of the most significant words in the Hebrew language.

Just in time for Advent, Christianity Today features a cover story on "The Mary We Never Knew," an article adapted from Scot McKnight's new book, The Real Mary: Why Evangelical Christians Can Embrace the Mother of Jesus.

Just in time for Advent, Christianity Today features a cover story on "The Mary We Never Knew," an article adapted from Scot McKnight's new book, The Real Mary: Why Evangelical Christians Can Embrace the Mother of Jesus.

The Right has had Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, and Sean Hannity, using a style that calls names as part of the entertainment of their shows (remember Limabaugh calling people “Femi-Nazis” and “Environmental Wackos”?). The Left has retaliated with Jon Stewart, Al Frankin, and Keith Olbermann, using satire and sometimes meanly poking fun as a means toward their political ends.

The Right has had Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, and Sean Hannity, using a style that calls names as part of the entertainment of their shows (remember Limabaugh calling people “Femi-Nazis” and “Environmental Wackos”?). The Left has retaliated with Jon Stewart, Al Frankin, and Keith Olbermann, using satire and sometimes meanly poking fun as a means toward their political ends.

Every evangelical today should thank God for the courage of Carl F. H. Henry. In the first half of the 20th Century, he was in the vanguard of a new group of Christians calling themselves the “New Evangelicals,” a group that wanted to move beyond the limitations of the Christian Fundamentalism of their day.

Every evangelical today should thank God for the courage of Carl F. H. Henry. In the first half of the 20th Century, he was in the vanguard of a new group of Christians calling themselves the “New Evangelicals,” a group that wanted to move beyond the limitations of the Christian Fundamentalism of their day.